The PE provides secured venture debt loans ranging from $2-15 million and has the ability to syndicate loans as large as $30 million for public companies. They are most interested in medical technology firms that are developing medical devices. The firm will only consider medtech companies that have products that are currently on the market. The firm will consider both US- and Canadian-based firms. The firm only considers funds that have at least $5 million in revenue, and will consider both private and public firms.

Hot Life Science Investor Mandate 3: PE Provides Secure Venture Debt Loans to Medtech

9 AugGorillas at the Table: Corporate Venture Capital

9 AugBy Jack Fuller, Business Development, LSN

The growing role of Corporate Venture Capital (CVC) in driving early stage enterprises in the life science sector has been well documented and dissected. The majority of corporate investments are structured in four forms: direct investments from the parent company, wholly owned subsidiaries, independent organizations with dedicated funds, and as limited partners in other funds. Understanding the type of corporate investment makes an enormous difference in the type of investment they are looking to make.

CVCs come in two flavors: internally focused on bolstering future technology prospects for the parent company, or externally focused on generating a solid return on the investment, with much less emphasis on the mission of the parent company. The primary strategy has shifted in recent years to favoring an externally focused approach. This is primarily due to the CVCs appreciating the fact that an initial investment in a company does not provide any significant advantage when it comes to acquiring or in-licensing the technology and the need to hold a diversified portfolio. It is particularly important to understand the CVCs as a viable source of capital, considering the changing landscape of entrepreneurial fundraising.

CVC funding is particularly beneficial for new ventures in the life sciences that operate in uncertain environments because they provide specialized assets and knowledge. Over 1/3 of active CVCs are healthcare focused, with Novartis Venture Funds, J&J Development Corp, SR One, Kaiser Permanente Ventures, Novo Venture, Merck Global Health Innovation Group, Lilly Ventures, MedImmune Ventures, Pfizer Venture Capital, Siemens Venture Capital, Roche Venture Fund and Google Ventures all being in the top 25 most active CVCs by number of deals in the last year. Additionally, studies have shown that financing rounds with a CVC involved tend to be significantly higher than non-CVC funded rounds. The innovation output of CVC-funded companies is also higher, as determined by the number of publications and patents.

Even more recently, CVCs have actually started co-investing in rounds with each other. Initially, this makes little sense as the parent companies are directly competing for the same technologies. However, as the CVC firms become more familiar with each other, they have begun to understand how each structures their deals, and are more comfortable sharing the table with another big name player. The shift toward independently-operating venture funds is big pharma’s response to keep the innovation pipeline flowing, with the decline of truly early stage VC funding. This is good news for early stage ventures, and should be carefully considered when planning a fundraising strategy.

A New Innovation Model for Incubators and Clusters

9 AugBy Max Klietmann, VP of Research, LSN

Innovative collaborative models are a defining part of the life science industry. We’re all familiar with alliances between big pharma and venture capital, the academic/commercial collaborations of the tech transfer space, and most recently, the development of early stage technologies by research hospitals. Currently, another emerging trend is poised to make a significant impact on the industry on a global scale: Global collaboration between research centers, incubators, and bioclusters in the form of organized therapy development alliances.

So what does it look like? The model, which has already been adopted by a group of six research institutions in the US and Europe, aims to integrate the entire value chain of the drug development pipeline – from discovery through distribution – by having all of the relevant stakeholders involved. Essentially, it is a collaborative strategy that puts research groups, universities, tech transfer offices, CROs, industry organizations, service providers, investors, and big pharma under a project umbrella that allows compounds to be quickly vetted, shepherded through the development and trial processes, and brought to market.

But what does this mean? Since these alliances are formalized groups aimed at advancing drug discovery and development on a global basis, it increases the chances of getting all the pieces in place to bring a drug to market several fold. It creates communication, standardized processes, and facilitates the sharing of best practices and resources. All of this is being made possible by enhanced information sharing and physical logistics, as well as data management capabilities. It translates to a new model for translational science commercialization, and could be a key answer to bridging the valley of death by bringing capital, service providers, and big pharma capabilities to emerging assets globally. This trend is likely to accelerate in the remainder of this year and into 2014, so prepare for a paradigm shift.

Better Understanding the Family Office

9 AugBy Michael Quigley, Research Analyst, LSN

Throughout the existence of this newsletter, LSN has discussed at length the trend of family offices moving towards direct investments in the life science space. However, family offices remain an obscure investment entity to many of our readers. In this article, I want to shed some light onto what exactly constitutes a family office, why their numbers are growing, and why they are such a crucial player in small- and medium-sized enterprises.

Throughout the existence of this newsletter, LSN has discussed at length the trend of family offices moving towards direct investments in the life science space. However, family offices remain an obscure investment entity to many of our readers. In this article, I want to shed some light onto what exactly constitutes a family office, why their numbers are growing, and why they are such a crucial player in small- and medium-sized enterprises.

To begin with, traditional wealth advisory and asset management firms provide clients with advice on investments, and may provide insight into insurance, tax, and budget-related decisions. Family offices, on the other hand, act as personal CFOs for ultra-high net worth families – and individuals handling all of these issues – as well as generational wealth management, philanthropic donations, legal issues and management of tangible assets. Each family office is unique in that its services are a function of the demands, skills and financial requirements of the family or individual whose money they manage.

These organizations exist primarily in two basic forms: Single Family Offices (SFOs) and Multi-Family Offices (MFOs). SFOs – as the name suggests – manage the finances for a single family or individual with a net worth generally over $100 million, with an average of around $600 million. MFOs, which have been recently gaining popularity, serve the same purpose, only they cater to the needs of multiple families with a minimum net worth around $20 million and an average of about $50 million.

The amount of capital held by family offices has been growing recently as a result of an increased demand for complete personalized financial management, SFO’s expanding to multiple clients, MFO’s lowering their asset requirements, and as traditional wealth managers (following the market demand) are offering more holistic services, transforming their business model to become MFO’s. Industry experts estimate that there are currently over 4,000 family offices in the United States alone, with well over $1 trillion in combined assets under management, making them a very significant source of private capital. (1)

Historically, family offices have been the funders of alternative assets such as venture capital and private equity funds, thus stimulating small- and medium-sized enterprises. As discussed in a previous LSN publication entitled “The Perfect Storm,” family offices have been discouraged by the performance of these alternative investments, and are beginning to bypass these types of funds and invest directly into privately-held companies themselves.

Many family offices involved in this trend are utilizing the skills and knowledge of the particular sector that made the family its fortune to identify strong investment opportunities, where they also have to ability to add value beyond capital. (2) What’s more, as long as family offices have been in existence, the majority have maintained a portion of their clients’ capital for the purpose of philanthropic allocations. Recently, philanthropy is becoming less of a donation and more of an investment focused on a measurable, positive social impact on society as a gauge of ROI. With this mindset, family offices are investing directly into industries like life science, where a scientific breakthrough could have a massive, lasting positive impact on a global scale. (3)

Family offices are both increasing in number and in involvement in direct private investments. There are many factors contributing to these two trends, and one of the biggest beneficiaries will be private companies fundraising for the growth of their enterprise. Family offices looking for an impact with their investments do not have the same standards for ROI as traditional investment firms who are under immense pressure to generate consistent returns by shareholders, and are therefore offering better terms with less stringent restrictions on time-to-exit than traditional private investors.

1 http://familyofficesgroup.com/Report.pdf

3 http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323551004578441002331568618.html

The Good, the Bad & the Ugly of Crowdfunding

1 AugBy Dennis Ford, CEO, LSN

The Good

I like crowdfunding for the life science arena because this industry already has a proven global audience that “votes with their feet” through a vast web of charitable platforms that raise money for research. Take, for instance, the crowds on any spring/summer weekend walking for this or that cure; the fact that everyone is in some way affected by disease makes these crowds not only readily available – but also relatively knowledgeable – potential investors.

Another unique value that these potential investors possess is that they emphatically want to change the world and help mankind. The fact is that almost everybody already donates in some capacity to research that aids in fighting disease, be it the extra dollar at grocery store checkouts or a planned donation to a charity or foundation. The question is whether or not crowdsourcing portals channel this worldwide source of capital in an adroit and compelling way. Basically, the net/net here is that crowd sourcing is already alive and well – and working. However, the biggest question is if the model can be transferred into the general population of potential investors made accessible by the jobs act, not just the accredited ones.

A side effect of this medium is that when you get onto the grid with your fundraising campaign, and are now in the mix and published, you are visible to everybody, which means an investor (or syndicate of investors) can come over the transom and write a big check and solve the fundraising issue by including you in a portfolio of life science assets.

So, the good is: it will work for launching a firm. However, you cannot raise over $1 million per year, and over $500k requires extensive filing and compliance, which can easily become an administrative headache.

The Bad

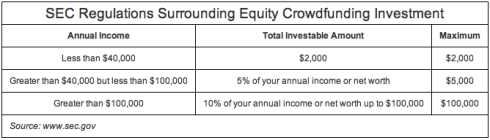

The main issue here is the numbers game that one has to play in order to reach a seven-figure goal, which translates to a large volume of required investors considering the SEC limits on investments in equity crowdfunding (see chart at the bottom of this article) – not to mention how to create dialogue and manage ongoing relationships with a group of investors of this size.

Crowdfunding is a paradigm shift. However, the ante into the game is where the biggest questions of all arise. Some sites are showing a very greedy edge, with equity positions ranging from 2 to 10+%, and/or a piece of the monies raised (between 5 -20%); that’s a pretty steep business model for a virtual company profile and a three minute video. As I look at the first batch of crowd sourcing portals and their associated business models, I am reminded of the Wild West and the stereotypical cast of characters. The mantras from the entrepreneurs who run these portals are pretty much all the same: “the risk to the investor is low because the investment dollar amount is low,” with the lofty slogan “the people will decide what makes its way into the market”.

Translating this into experimentally based life science technologies may be tricky, as the general public isn’t necessarily going to grok the subtleties of therapeutic biomarkers, or mechanisms of action, or physics-based, next-gen medical devices. The obvious candidates for this kind of funding, therefore, are easily understood healthcare IT solutions and/or simply comprehensible medical devices. The trick then for the therapeutic technologies is to take the high road, and use a similar easy-to-understand, high-level approach when pitching their technology.

Keeping it simple and using crowdfunding as a tactic for part of the strategy for early stage capital raising will be fine. However, it won’t be the full-blown solution to the industry’s capital needs.

The Ugly

How ugly can it be if you cannot see it yet, and where does crowd funding really fit? In my opinion, the fog has not been cleared on the regulatory side, and we have to wait for the rules and regulations to come down from on high. As of July 2013, no one knows what crowdfunding for equity investment currently really looks like!

I can speculate that because of the associated regulations, the best bet is as follows: if you need less than $500K to jump start your company, then you do not have to make the considerable investment of filing audited financial statements, which may also include compliance issues like keeping track of all communications through phone, email, and face-to-face meetings, etc., which translates to a very large administrative overhead.

The Bottom Line

The big challenge for the translational scientists is simplifying their message to a wider, less technically versed audience. Science needs to move through the experimental process step by step, and therefore, trying to get funding step by step is a reasonable approach if it is part of an overall fundraising strategy. What I mean by this is avoid the guardrail-to-guardrail, fits and starts approach, and have crowdfunding as a tactic in your overall strategy. Find small dollars to demonstrate efficacy, and then move on to the traditional groups and the new direct family offices and institutional investors for the larger capital needs.

At the end of the day, the scientist-entrepreneur has to understand that if he wants to play, he has to educate his or herself in the world of capital allocation, and the map that they use to do this has to be fresh and accurate and not dependent on the old models of fundraising, but rather reflect all the options, and how those options may map to the company’s needs over the next 5-7 years. The real take away from this discussion is that you need to create a strategy that covers all stages of your company’s financial needs by drawing the map of investor prospects for each stage.

The Family Office Love Affair with Medical Technology

1 AugBy Danielle Silva, Director of Research, Life Science Nation

Over the past couple of weeks, I’ve been speaking with many entrepreneurs developing medical devices regarding LSN’s upcoming Redefining Early Stage Investments Conference. What has struck a chord with many of these entrepreneurs is when I mention that we’re targeting non-traditional investors to attend our conference, such as family offices. Surprisingly, it’s not just because many of these medtech firms are looking to get in front of family offices – it’s because a good deal of them already have.

What I’ve heard from many of these companies developing medical devices is that family offices have been the first round of capital that they have received after gathering up funds from friends and family. This week, I spoke with a west coast based-company developing a medical device where this was the case, but have had countless conversations with other medtech companies that have echoed this trend.

If we take a deeper dive and further examine these two groups (early stage medical technology companies and family offices), they actually have a great deal in common. Early stage medical technology companies are often times in “stealth mode” – they don’t want other companies to know what they are doing, and certainly do not want their competitors replicating any IP that hasn’t been patented yet. Family offices are also incredibly secretive; as such, many of them don’t have websites, and their physical addresses typically can only be found by rifling through hundreds of SEC filings. The majority of the family offices that do have websites do not boast their portfolio companies on their website (like private equity funds or VCs typically do), or even mention what asset classes they typically allocate to. Thus, because family offices like to fly under the radar, they are a perfect fit for stealth mode medical device companies that want to keep their technology – and their investors – undisclosed.

What is also quite surprising is that these medical technology companies are not just receiving capital from small, single-family offices (SFOs) that are making one-off investments in the space; many are also being funded by multi-family offices (MFOs) that are institutional-quality investors, and have several hundred million in assets under management. These MFOs are actively looking to invest in a number of medical technology firms annually, and are not just making one-off investments in the space. I recently spoke with a family office based on the east coast that is actively looking to allocate to several medical technology companies before the year’s end.

So the question still remains – why are family offices so in love with early stage medical device companies? We’ve spoken at great lengths in previous articles about why family offices are attracted to the life science space as a whole, and we’ve touched upon the fact that these groups have a dual mandate – they are obviously focused on ROI, but also generally make philanthropic donations as well, and investing in life sciences fulfills this dual mandate. However, what makes investing in the medical device space so attractive to family offices is that understanding if a medical technology investment is attractive doesn’t require as much scientific knowledge compared to determining whether or not a therapeutic product is a sound investment. Also, what makes the medtech space more attractive than the therapeutics space for family offices is the fact that medical devices receive FDA approval much more quickly compared to therapeutics.

Another reason family offices have become more and more attracted to life science in general is that often times, a family member will be afflicted with a certain disease and thus the family office will attempt to push along the science in a particular area by investing in a company developing a product targeting this disease. This makes family offices particularly unique investors in the medical technology space – as most traditional investors in the space are not indication-oriented. The traditional investors in the medical technology space (like private equity firms and VCs) invest in a medical technology company based on the kind of device they are developing (for example they will look solely for companies developing active and implantable devices). As aforementioned, family offices are more indication-oriented, and so are less focused on how the technology functions and more concerned with what disease the device targets.

So if you’re an early stage company developing a medical device, it’s time to think outside the box, and start targeting non-traditional investors in the space like family offices. You should especially start to consider raising funds from this group of investors if you are a company in stealth mode that has not raised capital from institutional investors. From what I’ve been seeing and hearing over the past several weeks, it seems as if the family office love affair with investing in medical technology companies will only grow stronger.

Research Hospitals Poised To Disrupt Early Stage Innovation & Commercialization

1 AugBy Max Klietmann, VP of Research, LSN

In the domain of early stage biotech and med-tech innovation, point-of-care facilities are typically not where one would expect to find nascent translational technologies. However, some highly innovative hospitals and clinics are taking a novel approach to the healthcare arena by not only providing care, but also by actively driving new therapies into the marketplace. These entities are leveraging physicians and specialist staff to vet technologies and ideas in their earliest stages of development, and choosing the best to shepherd through the clinic and onto the market.

Why are they doing this? As hospitals are under increasing cost pressures, it serves as a natural way to create a competitive edge in the marketplace, and can create long-term commercial value, as well as a measurably higher standard of patient care. What makes this trend particularly interesting is that the vetting is done by boots-on-the-ground doctors – those who are addressing real-world medical challenges that they encounter on a regular basis. This is a significantly higher level of insight than any traditional provider of capital could bring to the table when evaluating commercial viability. Essentially, this means that they have an edge when it comes to picking winners, and that we can anticipate some of the leading sources of commercialized products in the future will be coming out of research hospitals.

One large hospital group that began implementing this strategy less than ten years ago serves as a perfect example. The Ohio-based institution has made tech commercialization a priority, and is finally seeing some very impressive results: the group has registered approximately 500 patents, and has created over 50 new companies. Those figures are the result of excellent vetting done by experienced specialists who understand the patient needs from the very beginning. This allows selection of the best science, which can then be backed by the capital of a major institution with a long-term orientation.

So what does it mean for the industry? First, this is a solution to one of the biggest issues in life sciences today: that there are so many emerging companies that it is difficult for anyone to know what is truly leading technology and how to vet it, leaving many early stage companies with great science to perish in the valley of death. Research hospitals can vet technologies better than anyone, and help to cut through much of the “noise” in the early stage space.

What’s more, these “pre-selected winners” can then access the capital required to move them past the early stages and into a position to be spun out or sold to a strategic buyer. This allows for more fair valuation, a partnership approach, access to resources on a massive scale, and will undoubtedly move science along faster and more effectively than by traditional means. This trend is poised to be a major disruptive factor for the life sciences at large, and will shift much of the industry dynamics.